As spring semester began, I continued my commitment to using graphic novels and comic books as powerful teaching tools for exploring critical social and historical issues with my high school students. Building on the successful foundation from fall semester’s monthly thematic posters, I expanded the approach to include inspirational quotes, deeper historical analysis, and broader explorations of diversity beyond superhero narratives. Each month’s poster, displayed outside my classroom door next to the entrance, created visible commitments to inclusive education while sparking conversations among students, staff, and visitors passing through the hallways.

January: Heroes Teaching Us About Service (Superman and Kamala Khan)

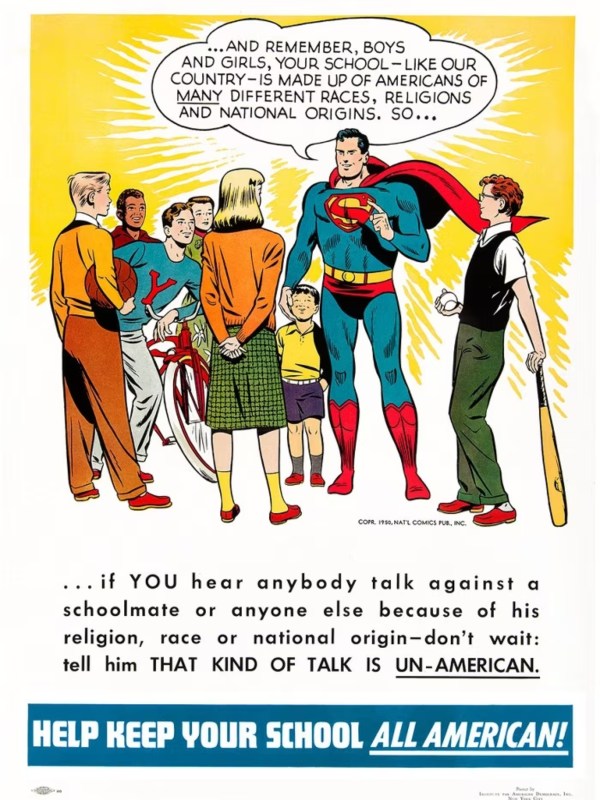

I launched the spring semester with a poster featuring powerful quotes from two heroes representing different eras and perspectives on heroism and service. The first image showed a classic 1950 Superman public service announcement where he tells a diverse group of children: “And remember, boys and girls, your school—like our country—is made up of Americans of many different races, religions and national origins. So… if you hear anybody talk against a schoolmate or anyone else because of his religion, race or national origin—don’t wait: tell him THAT KIND OF TALK IS UN-AMERICAN.” The poster concluded with “HELP KEEP YOUR SCHOOL ALL AMERICAN!” This vintage comic demonstrated how superheroes have long been used to promote tolerance and combat prejudice, speaking directly to young readers about their responsibility to stand up against discrimination.

The second quote came from Kamala Khan (Ms. Marvel), filled with comic book imagery showing diverse superheroes: “They taught me to always think about the greater good. To defend people who can’t defend themselves, even if it means putting yourself at risk.” Both quotes emphasized the core heroic principle that power and privilege come with responsibility to protect and defend others, particularly the most vulnerable. Students discussed how these messages span decades yet remain relevant, how different generations receive similar moral lessons through characters that reflect their contemporary world, and how the definition of “standing up for others” has evolved from Superman’s 1950s call to reject prejudiced talk to Kamala’s 21st-century understanding of intersectional justice and systemic risk.

For teachers looking to create similar inspirational quote posters, January offers an excellent opportunity to set the tone for the semester with messages about community, responsibility, and standing up for what’s right. Select quotes that resonate across different time periods to demonstrate how core values persist while their application evolves. The 1950 Superman PSA proves particularly powerful for its historical context; students are often surprised to learn that comics actively fought against prejudice during an era when schools and society remained deeply segregated. When choosing quotes, look for those that call students to action rather than passively consume heroic deeds. The best quotes make students reflect on their own choices and responsibilities within their communities. Consider pairing quotes from different eras or different types of heroes (alien Superman versus Pakistani-American Kamala) to show how heroic values transcend specific identities while remaining grounded in fighting injustice. Display these prominently at the semester’s beginning to establish expectations for classroom culture and to signal your commitment to social justice education throughout the coming months.

February: Truth, Representation, and Historical Complexity (Black History Month)

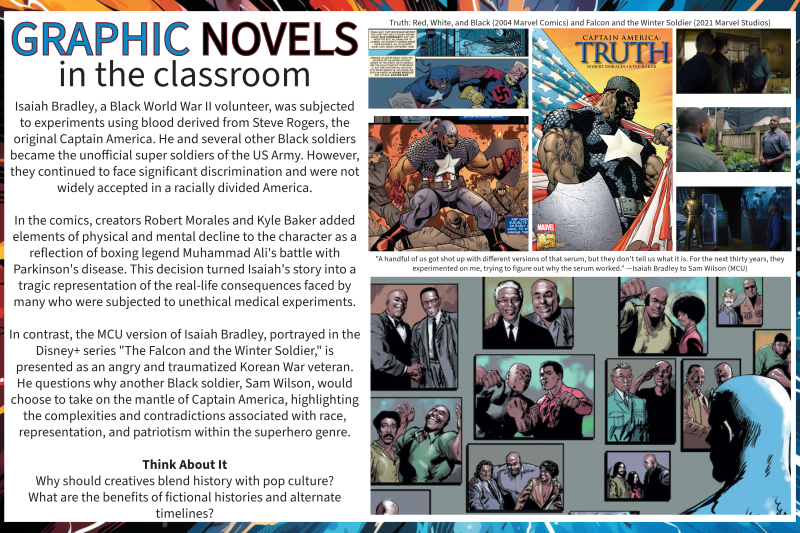

February’s focus aligned with Black History Month through an examination of Isaiah Bradley’s story in both the 2004 Marvel Comics series “Truth: Red, White, and Black” and the 2021 Disney+ series “The Falcon and the Winter Soldier.” This poster allowed us to explore how comics can tackle difficult historical truths, the ethics of blending real history with fictional narratives, and the importance of acknowledging uncomfortable aspects of American history. The poster explained how Isaiah Bradley, a Black World War II volunteer, was subjected to experiments using blood derived from Steve Rogers (the original Captain America). Bradley and several other Black soldiers became unofficial super soldiers but continued facing significant discrimination in a racially divided America, never receiving recognition for their service or sacrifice.

Students learned how comic creators Robert Morales and Kyle Baker added elements of physical and mental decline to Bradley’s character, drawing direct parallels to boxing legend Muhammad Ali’s battle with Parkinson’s disease. This decision transformed Isaiah’s story into a tragic representation of the real consequences faced by many subjected to unethical medical experiments, echoing the horrors of the Tuskegee Syphilis Study. We compared this comic version with the MCU’s portrayal in “The Falcon and the Winter Soldier,” where Isaiah appears as an angry and traumatized Korean War veteran questioning why another Black soldier (Sam Wilson) would choose to take on the Captain America mantle. The poster’s “Think About It” questions sparked rich discussions: “Why should creatives blend history with pop culture? What are the benefits of fictional histories and alternate timelines?” Students grappled with whether using real historical trauma in fictional superhero narratives honors or exploits those experiences, whether reaching younger audiences through popular media keeps important historical lessons alive, and how representation asks not just “are marginalized groups present?” but “how are their stories being told, and who benefits?”

Teachers developing Black History Month resources should recognize that superficial celebration of “Black excellence” without acknowledging historical and ongoing oppression provides incomplete education. The Isaiah Bradley story offers a powerful vehicle for discussing medical racism, the exploitation of Black soldiers, and how patriotism and national identity become complicated when the nation fails to extend full citizenship to all its people. When creating these materials, include both the comic book version and contemporary media adaptations to show students how stories evolve across different formats and time periods. Research the real historical events that inspired fictional narratives; in this case, connections to the Tuskegee experiments, unethical military medical testing, and the broader context of Black soldiers’ treatment during and after World War II provide essential background. Consider how to present difficult historical material in age-appropriate ways that don’t sanitize trauma but also don’t sensationalize suffering. The goal is helping students understand systemic injustice and its long-term consequences while recognizing how marginalized communities have resisted and persevered. Coordinate with history and English teachers to reinforce these themes across multiple classes, and be prepared for emotional responses as students confront uncomfortable truths about American history.

March: Beyond the Femme Fatale (Women’s History Month)

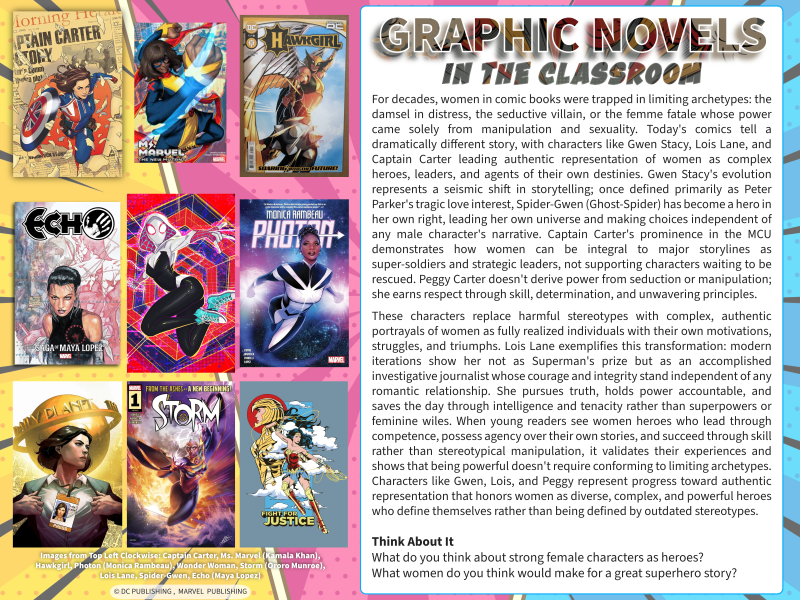

March’s Women’s History Month poster examined how modern comics have moved beyond limiting archetypes to create authentic female representation. For decades, women in comic books were trapped as damsels in distress, seductive villains, or femme fatales whose power came solely from manipulation and sexuality. The poster featured characters like Gwen Stacy (Spider-Gwen/Ghost-Spider), Lois Lane, Captain Carter (Peggy Carter), Kamala Khan (Ms. Marvel), Monica Rambeau (Photon), Wonder Woman, Storm (Ororo Munroe), Hawkgirl, and Echo (Maya Lopez), demonstrating the breadth of complex female heroes now leading their own narratives.

Students analyzed Gwen Stacy’s evolution as particularly significant; once defined primarily as Peter Parker’s tragic love interest, Spider-Gwen has become a hero in her own right, leading her own universe and making choices independent of any male character’s narrative. Similarly, Captain Carter’s prominence in the MCU demonstrates how women can be integral to major storylines as super-soldiers and strategic leaders rather than supporting characters waiting to be rescued. The poster emphasized that these characters replace harmful stereotypes with complex, authentic portrayals of women as fully realized individuals with their own motivations, struggles, and triumphs. Lois Lane exemplifies this transformation; modern iterations show her not as Superman’s prize but as an accomplished investigative journalist whose courage and integrity stand independent of any romantic relationship. The “Think About It” questions encouraged personal reflection: “What do you think about strong female characters as heroes? What women do you think would make for a great superhero story?” Female students particularly engaged with discussions about how seeing women heroes who lead through competence, possess agency over their own stories, and succeed through skill rather than stereotypical manipulation validates their own experiences.

Teachers creating Women’s History Month resources should embrace the opportunity to move beyond tokenistic inclusion of female characters and explore the rich tapestry of women’s historical portrayals and their ongoing evolution. The “femme fatale versus complex hero” framework serves as an engaging entry point for discussing how breaking free from limiting gender stereotypes benefits everyone by expanding the range of stories we can tell. When selecting characters, prioritize those with agency and independence, showcasing women who are defined by their own accomplishments rather than just their relationships with male characters. Include a diverse array of women representing various races, abilities, body types, and backgrounds to highlight that “women’s representation” is vibrant and multi-faceted. Pairing historical examples of past portrayals with contemporary successes can inspire students to celebrate progress while recognizing that there’s still work to be done. Encourage students to identify real women in their own lives whose stories deserve heroic recognition, thus expanding the conversation to include courageous, intelligent, and resilient figures beyond fiction. Be ready to address the ongoing challenge of hypersexualization in comics while also celebrating the narrative improvements, helping students differentiate between female characters created for male audiences and those crafted by and for women readers.

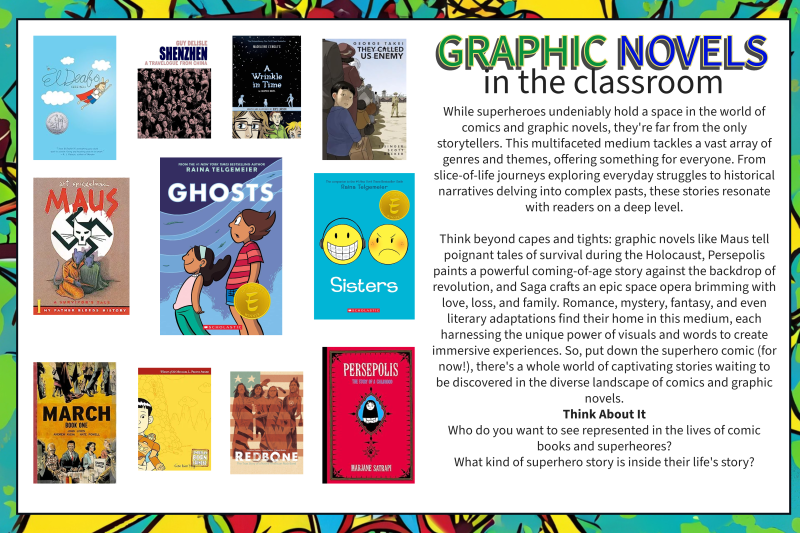

April: Graphic Novels Telling Real-Life Stories

April’s poster circled back to reinforce the message that graphic novels extend far beyond superhero narratives, specifically highlighting works that tell real-life stories and explore diverse human experiences. While superheroes undeniably hold space in comics and graphic novels, they’re far from the only storytellers. This poster showcased works like “El Deafo” (Cece Bell’s memoir about growing up deaf), “They Called Us Enemy” (George Takei’s Japanese American internment experience), “A Wrinkle in Time” (Hope Larson’s adaptation), “Shenzhen” (Guy Delisle), “Maus” (Art Spiegelman’s Holocaust narrative), “Ghosts” (Raina Telgemeier), “Sisters” (Raina Telgemeier), “March” (John Lewis’s civil rights memoir), “American Born Chinese” (Gene Luen Yang), “Redbone” (Christian Staebler), and “Persepolis” (Marjane Satrapi’s coming-of-age story during the Iranian Revolution).

The poster emphasized that this multifaceted medium tackles vast arrays of genres and themes, offering something for everyone. From slice-of-life journeys exploring everyday struggles to historical narratives delving into complex pasts, these stories resonate with readers on deep levels. Students explored how “Maus” tells poignant tales of survival during the Holocaust, how “Persepolis” paints powerful coming-of-age stories against the backdrop of revolution, and how works like “March” craft epic narratives of the civil rights movement brimming with courage, sacrifice, and determination. The month emphasized that romance, mystery, fantasy, and literary adaptations all find their home in this medium, each harnessing the unique power of visuals and words to create immersive experiences. The “Think About It” questions remained consistent with January: “Who do you want to see represented in the lives of comic books and superheroes? What kind of superhero story is inside their life’s story?” By April, students’ answers had evolved considerably, proposing specific untold stories about immigrant experiences, neurodivergent protagonists, rural poverty, climate anxiety, and countless other perspectives still underrepresented in mainstream publishing.

Teachers using graphic novels to explore diverse real-life stories should recognize that memoirs and historical narratives in graphic novel format provide powerful scaffolding for reluctant readers or students who struggle with dense prose. The visual component helps students access complex historical events and personal experiences that might overwhelm them in traditional text format. When creating end-of-semester resources, showcase the breadth of the medium to counter any lingering perception that graphic novels are purely entertainment or “less serious” than traditional literature. Highlight award-winning works (Pulitzer Prize for “Maus,” National Book Award for “March”) to emphasize literary legitimacy. Consider creating a classroom library or recommended reading list featuring diverse graphic novels so students can continue exploring beyond required reading. April provides an excellent opportunity to reflect on the full semester’s themes, connecting the representation work from earlier months to the broader landscape of visual storytelling. Encourage students to create their own graphic narratives about personal experiences, family histories, or community stories, applying the literacy skills they’ve developed while analyzing professional works. These resources work particularly well when coordinated with school librarians who can recommend age-appropriate graphic novels, purchase new titles for the collection, and create displays promoting diverse visual narratives. End the semester by inviting students to share which graphic novels resonated most deeply with them and why, reinforcing that everyone’s story matters and that visual storytelling continues expanding to embrace more voices and more truths about our complex world.

Reflections and Practical Implementation

Throughout spring semester, displaying these monthly posters outside my classroom door continued serving multiple purposes beyond my enrolled students’ education. The hallway location meant every student, teacher, and visitor passing by encountered messages about heroism, representation, historical truth, and diverse storytelling multiple times daily. The January quotes poster sparked particularly interesting conversations; several students from other classes stopped to photograph the Superman and Kamala Khan quotes, with some mentioning they’d never thought about old comics addressing discrimination. The February Isaiah Bradley poster generated the most questions from staff members, with several teachers asking for resources to incorporate similar content into their own classes.

For educators interested in creating similar monthly resources for spring semester, I recommend thinking about narrative arc across the months. Spring semester began with inspirational calls to action (January’s quotes about defending others), moved into confronting difficult historical truths (February’s exploration of medical racism and exploitation), celebrated progress and evolving representation (March’s focus on complex female characters), and concluded with broadening horizons beyond the superhero genre entirely (April’s showcase of real-life graphic novel stories). This progression mirrors many students’ journeys from enthusiastic but uncritical consumers of media to thoughtful analysts who question whose stories get told, how they’re told, and what perspectives remain marginalized. When designing your own poster series, consider what journey you want students to take across the semester and how each month’s theme builds toward that destination. Maintain consistent visual design so students recognize the series while varying content enough to sustain interest. Most importantly, don’t treat these posters as standalone decorations; reference them in lessons, use them as discussion prompts, encourage students to suggest future topics, and create opportunities for deeper engagement beyond hallway viewing. The visible commitment to inclusive education through these monthly posters signals to the entire school community that representation matters, that difficult conversations belong in educational spaces, and that popular culture provides legitimate vehicles for exploring the most important questions about justice, identity, and our shared humanity.

This is part of my Comics in the Classroom series where I look at the importance of the comic book industry and how to use them as resources in the classroom. To read more check out my other posts. (Link)

You must be logged in to post a comment.