What if I told you that Europe’s most tolerant society existed in medieval Spain—500 years before the Enlightenment? While most of medieval Europe struggled with illiteracy, religious warfare, and intellectual stagnation, the Iberian Peninsula was home to a remarkable civilization that would become the bridge between ancient wisdom and Renaissance rebirth.

This October, as we celebrate Hispanic Heritage Month, it’s time we expanded our understanding of Spanish history beyond the familiar narrative of 1492 and Columbus. The real story begins much earlier, in 711 CE, when Islamic armies crossed the Strait of Gibraltar and transformed the peninsula into Al-Andalus—a name that would become synonymous with learning, tolerance, and cultural brilliance for nearly eight centuries.

The Conquest That Changed Everything

When Tariq ibn Ziyad led the first Islamic forces into Iberia in 711 CE, few could have predicted the extraordinary civilization that would emerge. Unlike the destructive conquests that characterize much of medieval history, the Islamic takeover of Spain proved remarkably different. Rather than imposing a foreign culture, the new rulers created something unprecedented: a society where Muslims, Christians, and Jews not only coexisted but collaborated to create one of history’s most sophisticated civilizations.

By the 8th century, Córdoba had become the largest city in Europe, rivaling Constantinople and Baghdad as a center of learning and culture. Its Great Mosque, with its famous red-and-white striped arches, stood as a symbol of this new world—built on the site of a Visigothic church, incorporating Roman columns, and designed with Islamic innovations that would influence architecture for centuries to come.

Europe’s Center of Learning

While European monasteries struggled to preserve fragments of classical knowledge, Al-Andalus became a vast intellectual laboratory. The caliphs of Córdoba established libraries that dwarfed anything in Christian Europe. The library of Caliph Al-Hakam II (961-976 CE) reportedly contained over 400,000 volumes—at a time when most European monasteries owned fewer than 100 books total.

But numbers tell only part of the story. What made Islamic Spain truly revolutionary was its approach to knowledge. Rather than merely preserving ancient texts, scholars in Al-Andalus actively expanded upon them. They didn’t just read Aristotle—they debated him, corrected him, and built new philosophical systems that would eventually reshape European thought.

The Translation Revolution

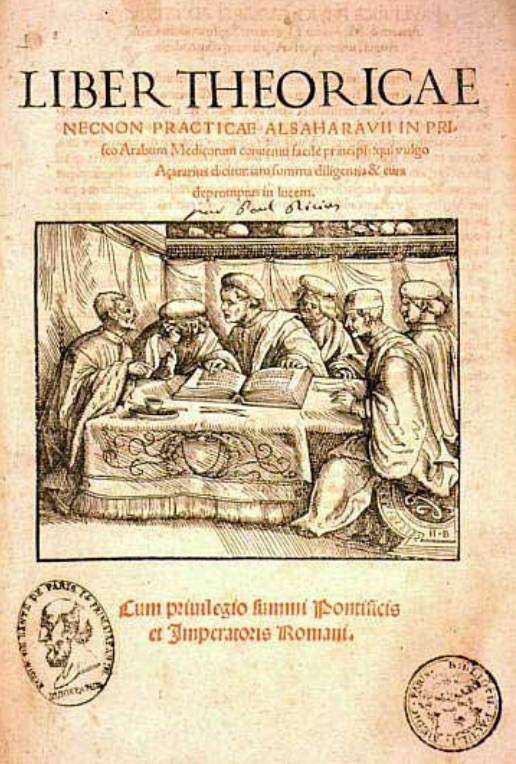

Perhaps nowhere was this intellectual dynamism more evident than in the famous translation schools of Toledo, Córdoba, and Seville. Here, in rooms filled with Arabic, Hebrew, and Latin texts, scholars engaged in one of history’s most ambitious intellectual projects: the systematic translation and preservation of human knowledge.

The process was remarkably collaborative. A typical translation might begin with a Jewish scholar fluent in Arabic translating a Greek philosophical text into Hebrew, followed by a Christian scholar rendering it into Latin, with Muslim scholars providing commentary and analysis throughout. This wasn’t just translation—it was intellectual archaeology, recovering and revitalizing the wisdom of antiquity.

Consider the journey of Aristotle’s works: lost to most of Europe during the Dark Ages, preserved and expanded by Islamic scholars like Averroes (Ibn Rushd) in Córdoba, then retranslated into Latin in the schools of Toledo, these texts would eventually reach Paris and Oxford, where they would revolutionize European philosophy and help trigger the Renaissance.

Giants of Islamic Spain

The intellectual giants of Al-Andalus reads like a who’s who of medieval achievement. Averroes (1126-1198), born in Córdoba, didn’t just comment on Aristotle—he corrected him, developing new theories about the relationship between faith and reason that would influence both Islamic and Christian thought for centuries.

Abbas ibn Firnas (810-887) conducted some of the world’s first experiments in human flight, centuries before Leonardo da Vinci. In Córdoba, he built and tested wings that allowed him to glide through the air—an achievement that would have seemed like magic to most of medieval Europe.

Al-Zahrawi (936-1013), known in Latin as Albucasis, revolutionized surgery and medicine. His illustrated surgical manual became the standard medical textbook in European universities for over 500 years. The surgical instruments he designed were so advanced that many remained unchanged until the modern era.

Ibn Hazm (994-1064) wrote “The Ring of the Dove,” a sophisticated analysis of love and human relationships that reads like a medieval psychology textbook. His work on Islamic jurisprudence and theology influenced legal thinking across the Islamic world.

Beyond the Palace Walls

This wasn’t just elite culture confined to royal courts. The prosperity and tolerance of Al-Andalus created opportunities for innovation at every level of society. Engineers developed sophisticated irrigation systems that turned southern Spain into an agricultural paradise. Craftsmen perfected techniques in metalwork, textiles, and ceramics that would define Spanish artistic traditions for centuries.

Markets in cities like Granada and Seville bustled with merchants speaking Arabic, Hebrew, Latin, and emerging Romance languages. A customer might buy spices from a Muslim trader, commission jewelry from a Jewish artisan, and discuss philosophy with a Christian scholar—all in the same afternoon.

The Science Revolution

While European scholars debated how many angels could dance on the head of a pin, scientists in Al-Andalus were measuring the circumference of the Earth, cataloging stars, and developing new mathematical concepts. The word “algebra” comes from the Arabic “al-jabr,” reflecting the Islamic world’s contributions to mathematics.

Medical schools in Córdoba and Granada taught anatomy, surgery, and pharmacology using methods that wouldn’t appear in the rest of Europe for centuries. Hospitals in Islamic Spain included wards for mental illness—a humanitarian innovation that contradicted medieval European beliefs about madness as divine punishment.

A Legacy Larger Than Spain

The achievements of Islamic Spain extended far beyond the Iberian Peninsula. When Alfonso X “the Wise” established his translation schools in the 13th century, he was building on centuries of Islamic Spanish tradition. The knowledge preserved and expanded in Al-Andalus would flow into medieval European universities, laying the groundwork for the Renaissance.

Even the Spanish language bears witness to this remarkable heritage. Over 4,000 Spanish words derive from Arabic, from everyday terms like “alcohol” and “sugar” (azúcar) to place names like Gibraltar (Jabal Tariq) and Guadalquivir (Wadi al-Kabir).

Lessons for Hispanic Heritage Month

As we celebrate Hispanic Heritage Month, the story of Islamic Spain reminds us that Spanish identity has always been beautifully complex. The Spain that would eventually colonize the Americas was itself the product of an extraordinary cultural synthesis—Islamic, Jewish, and Christian traditions creating something entirely new.

This history challenges us to think more broadly about what “Hispanic” means. It’s not just the story of European conquest and Catholic mission, but also the legacy of Islamic scholarship, Jewish philosophy, and the remarkable experiment in tolerance that flourished in medieval Spain.

Understanding Al-Andalus helps us appreciate that diversity and cultural exchange have always been sources of strength, not weakness. The greatest achievements of Spanish civilization emerged not from cultural purity, but from the creative tensions and collaborations between different traditions.

The next time you walk through a Spanish courtyard with its central fountain, admire the geometric patterns in Spanish tilework, or use a Spanish word of Arabic origin, remember: you’re experiencing the living legacy of Europe’s most successful multicultural society.

What aspects of Islamic Spain’s legacy do you see in modern Hispanic culture? How might understanding this history change the way we approach cultural diversity today?

This is the first in a series exploring the multicultural roots of Spanish civilization. Next week, we’ll examine how Muslims, Jews, and Christians created their remarkable culture of convivencia—living together—in medieval Spain.

You must be logged in to post a comment.