Today’s conversation with my freshmen about altruistic and culturally competent leadership reminded me why I love teaching government and civics. When we stripped away all the complexity, the students kept circling back to something fundamental: real leaders care about other people more than themselves.

This isn’t the leadership we see valorized in movies or celebrated in corporate motivational posters. It’s quieter, harder, and infinitely more important.

Protection as Purpose

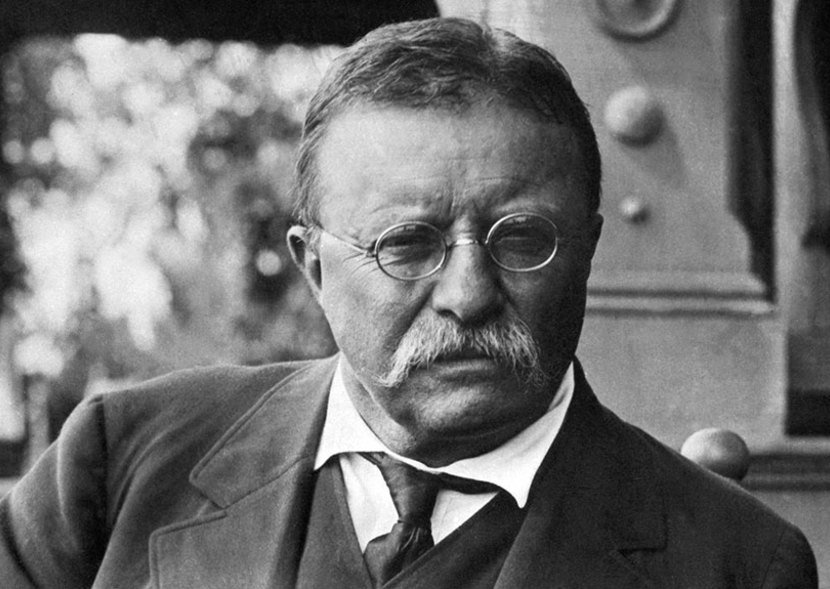

Theodore Roosevelt understood that leadership meant standing between danger and those who depend on you. He wrote, “The credit belongs to the man who is actually in the arena, whose face is marred by dust and sweat and blood.” But what’s often missed in that famous passage is its context—Roosevelt wasn’t celebrating personal glory. He was describing someone who fights for something beyond themselves, who takes the bruises so others don’t have to.

When I ask students what makes someone a leader, they often start with confidence or charisma. But when we dig deeper, they realize the leaders they actually respect are the ones who protected them—the older sibling who stood up to a bully, the teacher who believed in them when others didn’t, the coach who made sure everyone got playing time.

Protection isn’t just physical. It’s creating space for others to be themselves, to make mistakes, to grow. Ulysses S. Grant, who knew something about leading people through impossible circumstances, demonstrated this throughout his military career. He wrote to his wife Julia, “The friend in my adversity I shall always cherish most.” Grant understood that loyalty and protection flowed both ways—that a leader’s job was to ensure no one was left behind, even when it would be easier to cut losses and move forward.

Creating More Leaders, Not Followers

The second principle we discussed was perhaps the most counter-intuitive: a leader’s job is to create more leaders, not to accumulate followers. This is where leadership becomes truly altruistic—you’re working to make yourself unnecessary.

Eleanor Roosevelt captured this beautifully: “A good leader inspires people to have confidence in the leader, a great leader inspires people to have confidence in themselves.” Every time I read that quote, I think about the students who’ve moved through my classroom and gone on to lead in their own communities. The ones I’m proudest of aren’t the ones who still need my guidance—they’re the ones who don’t.

Tolkien understood this deeply in his portrayal of leadership in The Lord of the Rings. Gandalf spends the entire narrative working to empower others—teaching Frodo, believing in Sam, encouraging Aragorn to claim his destiny. His greatest moments aren’t displays of his own power but acts of faith in others’ potential. As he says, “All we have to decide is what to do with the time that is given us.” Leadership is helping others make that decision for themselves.

The Radical Act of Empathy

Which brings us to the third pillar: empathy and kindness. Not as soft skills or nice-to-haves, but as the engine that drives everything else.

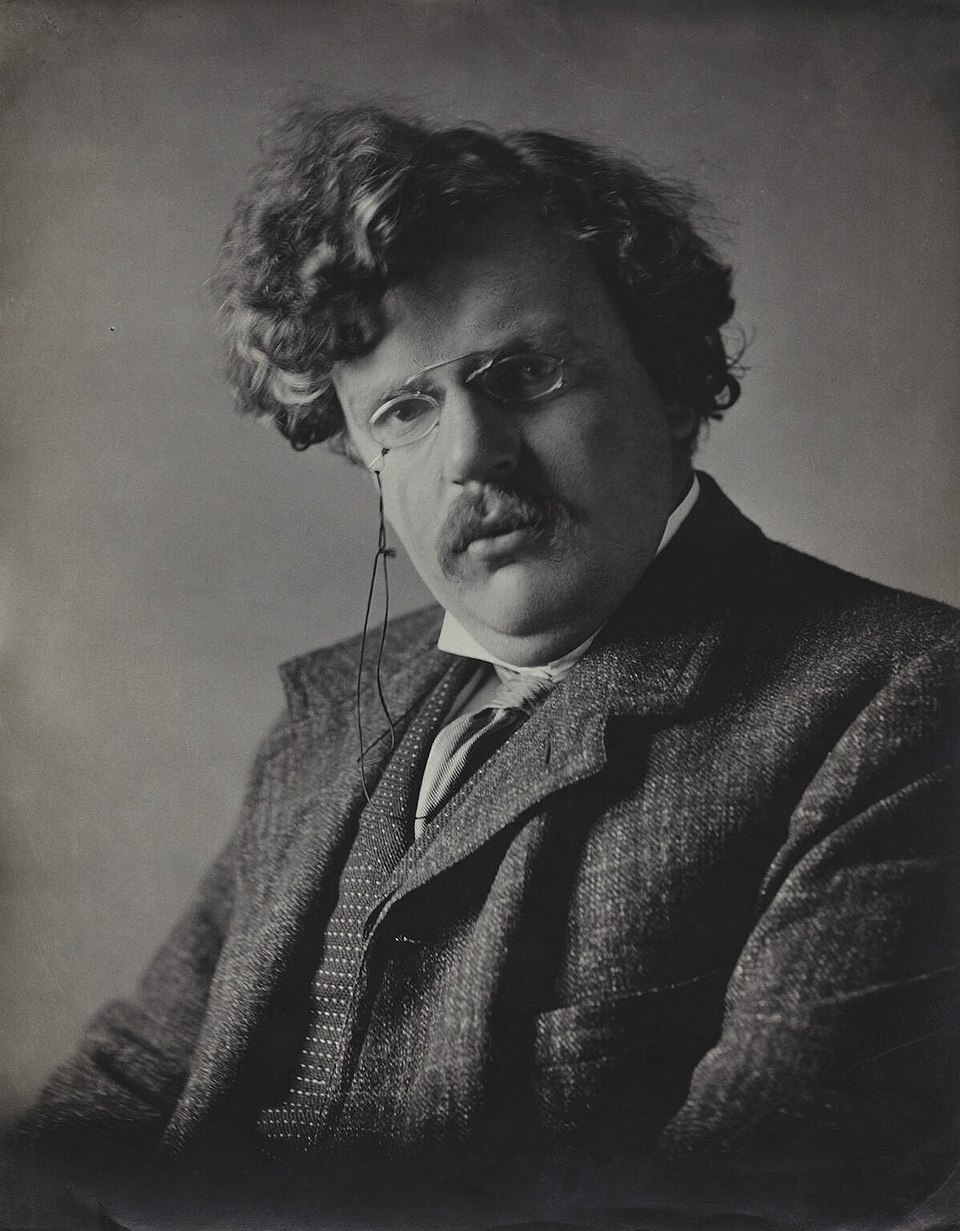

G.K. Chesterton wrote, “(My faith) tells us to love our neighbors, and also to love our enemies; probably because generally they are the same people.” There’s profound leadership wisdom here. Cultural competence—which we discussed at length today—isn’t about learning a checklist of do’s and don’ts for different groups. It’s about genuinely seeking to understand people whose experiences differ from your own, even (especially) when it’s uncomfortable.

Theodore Roosevelt, for all his flaws, grasped this in his own way: “Nobody cares how much you know, until they know how much you care.” Students can smell inauthenticity from miles away. They know when you’re going through the motions versus when you genuinely value them as individuals.

Empathy in leadership means making yourself vulnerable to others’ pain. It means their struggles become your struggles. Grant demonstrated this repeatedly during the Civil War, personally ensuring that surrendered Confederate soldiers could keep their horses for spring plowing, that officers kept their side arms, that defeated men could return home with dignity. He could have crushed them—he chose to see them as human beings instead.

The Daily Practice

What I emphasized to my students today is that leadership isn’t a position or a title—it’s a practice. It’s the daily decision to:

- Speak up when someone is being excluded or diminished

- Share credit and accept blame

- Listen more than you talk

- Ask “How can I help?” instead of “What can you do for me?”

- Recognize that your community is only as strong as its most vulnerable members

Eleanor Roosevelt put it perfectly: “You gain strength, courage, and confidence by every experience in which you really stop to look fear in the face. You are able to say to yourself, ‘I lived through this horror. I can take the next thing that comes along.’” Leadership is doing that hard thing, then turning around and helping others through it.

Tolkien’s Sam Gamgee—who represents servant leadership in its purest form—says near the end of the quest: “I can’t carry it for you, but I can carry you.” That’s it. That’s the whole thing. A leader doesn’t take away others’ burdens or fight their battles for them, but walks beside them, ready to offer strength when theirs fails.

For Our Classrooms

As educators, we model leadership every day whether we intend to or not. Our students are watching to see if we mean what we say about empathy, about valuing others, about lifting people up. They’re checking whether we protect the vulnerable students or ignore them, whether we create space for all voices or just the loudest ones, whether we treat their struggles with genuine concern or performative sympathy.

The question I posed to my freshmen—and the one I pose to myself constantly—is this: Are you leading in a way that makes the world bigger or smaller for others? Do you expand possibilities or contract them? Do you leave people more capable than you found them?

Chesterton wrote, “How much larger your life would be if your self could become smaller in it.” That’s the paradox of leadership: you become more influential by centering yourself less. You gain authority by giving it away. You become essential by teaching others they don’t need you.

Roosevelt, Grant, Eleanor, Tolkien, Chesterton—each understood in their own way that leadership stripped down to its essence is about valuing other people. Not as means to your ends, not as followers for your cause, but as inherently worthy of protection, development, and compassion.

That’s the leadership worth teaching. That’s the leadership worth practicing.

Celebrating Positivity is a monthly post that suggests ideas for classroom activities related to Heritage Months, Famous Birthdays, and Positive Historical Events.

You must be logged in to post a comment.