Between Hammer and Anvil: Ukraine’s Path From World War I Through Soviet Oppression

Introduction

The vast steppes and rich farmlands of Ukraine have often been described as the “breadbasket of Europe,” but during the tumultuous period spanning the First World War through the interwar years, this fertile region became one of history’s most contested and bloodied battlegrounds. While Western narratives often treat this period as a mere prelude to World War II or a footnote to the Russian Revolution, for Ukrainians, Cossacks, and other peoples of the region, these decades represented an existential struggle that would fundamentally reshape their societies and collective identities.

The collapse of empires during World War I briefly opened a window for Ukrainian self-determination, only for it to be violently shut by competing powers. What followed was a devastating cycle of occupation, rebellion, and repression that culminated in some of the 20th century’s worst humanitarian catastrophes, including the Holodomor famine and the brutal suppression of the Cossack communities. This forgotten chapter in European history reveals how great power politics and ideological extremism combined to crush the aspirations of entire peoples and set the stage for conflicts that continue to reverberate today.

Ukraine on the Eve of World War I: A Nation Without a State

Before World War I erupted in 1914, Ukraine did not exist as an independent state. Instead, its territories were divided between two empires: approximately 80% of ethnic Ukrainian lands fell under Russian imperial rule, while the western regions of Galicia, Bukovina, and Transcarpathia belonged to the Austro-Hungarian Empire. This division had profound implications for Ukrainian national identity, as different imperial policies shaped distinct cultural and political trajectories.

In Russian-controlled Ukraine, a policy of Russification sought to suppress Ukrainian cultural and linguistic distinctiveness. The Ukrainian language was officially banned from schools and publications in 1876 under the Ems Ukaz, and Ukrainian national aspirations were treated as a threat to imperial unity. Despite these restrictions, a Ukrainian national movement had emerged by the late 19th century, advocating for cultural rights and, among some circles, political autonomy.

In Austrian-controlled Galicia, Ukrainians (often called Ruthenians) experienced somewhat greater cultural freedom. The Habsburg Empire’s multinational structure allowed for Ukrainian-language education and publications, and Ukrainian political parties openly participated in provincial politics. However, Ukrainians still faced discrimination from the locally dominant Polish aristocracy, creating resentment and nationalist sentiment.

The Cossack communities, with their tradition of military service and relative autonomy, occupied a complex position within the Russian Empire. Once independent warrior communities known for defending the borderlands, many Cossack hosts had been integrated into imperial structures as privileged military units. But this integration came with increasing Russian control, especially after Cossack involvement in anti-imperial revolts led to restrictions on their traditional freedoms.

World War I: The Great Catalyst of Change

When war erupted in 1914, Ukrainians found themselves in a tragic position – forced to fight against each other in the armies of opposing empires. Ukrainian conscripts in the Russian army faced Ukrainian conscripts from Galicia in the Austro-Hungarian forces. The eastern front cut directly through Ukrainian ethnic territories, turning the region into a devastating battlefield.

The Russian Empire initially made gains in Galicia, occupying Lviv and other major cities. During this occupation, Russian authorities attempted to suppress Ukrainian cultural institutions, viewing them as Austro-Hungarian fifth columns. Thousands of Ukrainian activists were arrested and deported to Siberia. Simultaneously, Austro-Hungarian authorities in the remaining Ukrainian territories suspected their Ukrainian population of pro-Russian sympathies, leading to mass internment of suspected “Russophiles” in notorious camps like Talerhof, where thousands died from disease and mistreatment.

However, the fortunes of war soon shifted. Following the Brusilov Offensive of 1916 and Russia’s subsequent military collapse, German and Austro-Hungarian forces pushed eastward, occupying much of Ukraine by 1918. The war had devastated the region economically – agriculture was disrupted, cities were damaged, and transportation networks were destroyed. More importantly, it had delegitimized the old imperial orders and created space for revolutionary change.

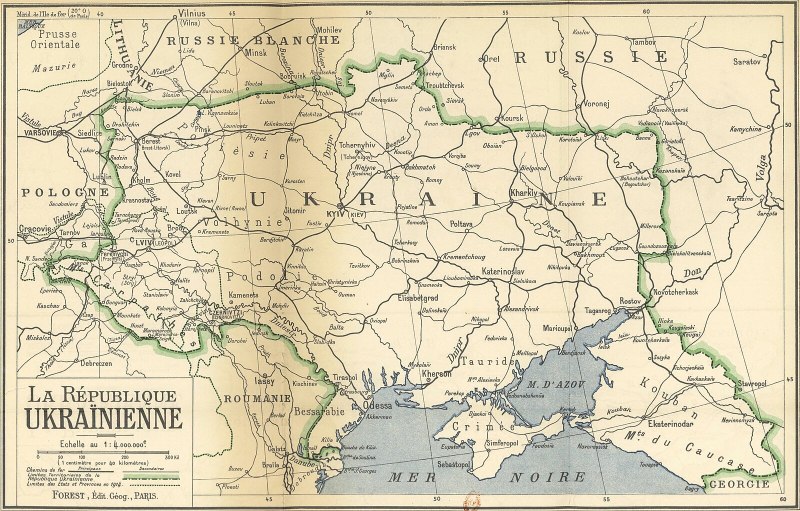

Map excerpt from Mémoire sur l’indépendance de l’Ukraine, présenté à la Conférence de la paix par la Délégation de la République ukrainienne (1919) that was created following the Treaty of Versailles negotiations.

The Ukrainian Revolution: A Brief Moment of Possibility

The February Revolution of 1917 in Russia created a power vacuum that Ukrainian leaders quickly moved to fill. In March 1917, Ukrainian political figures in Kyiv established the Central Rada (Council), initially seeking autonomy within a democratic Russian federation. Led by historian Mykhailo Hrushevsky, the Rada gained widespread support and began building Ukrainian governmental institutions.

As Russia descended further into chaos, the Rada declared the Ukrainian People’s Republic (UNR) in November 1917, still theoretically within a federated Russia. However, after the Bolshevik coup in Petrograd, the UNR declared complete independence in January 1918. Similarly, after the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Empire in late 1918, Ukrainians in Galicia established the Western Ukrainian People’s Republic (ZUNR).

These nascent Ukrainian states faced enormous challenges. The UNR fought against Bolshevik forces invading from Russia, while simultaneously negotiating with the Central Powers for recognition and support. The ZUNR immediately entered into conflict with Polish forces over control of Galicia, particularly the city of Lviv. In January 1919, the two Ukrainian republics proclaimed unification, but this unity remained largely symbolic as both struggled for survival against multiple enemies.

For the Cossack communities, particularly the Don and Kuban Cossacks whose territories bordered Ukraine, this period also offered a brief opportunity for autonomy. The Don Cossacks established their own republic in 1918, while the Kuban Cossacks (many of whom identified as Ukrainian) created the Kuban People’s Republic with close ties to the UNR.

The Wars After the War: Ukraine’s Struggle for Survival

The period from 1918 to 1921 is often called the “Ukrainian War of Independence,” but this term understates the complexity of the conflict. In reality, multiple wars raged simultaneously across Ukrainian territories, involving at least six major forces:

- The Ukrainian People’s Republic forces led by Symon Petliura

- The Western Ukrainian People’s Republic army

- The Russian Bolshevik Red Army

- The White Russian anti-Bolshevik forces

- Polish military forces

- Anarchist forces led by Nestor Makhno

Additionally, French, Greek, and Romanian troops intervened in southern Ukraine, while German and Austro-Hungarian occupation forces remained until late 1918. This chaotic situation was complicated further by the presence of numerous warlords and bandits exploiting the disorder.

Ukrainian civilians suffered terribly during this period. Kyiv changed hands sixteen times in two years. Pogroms against Jewish communities occurred throughout the region, with the worst violence perpetrated by White Russian forces, though Ukrainian nationalist forces also participated in anti-Jewish violence in some areas. Meanwhile, the Bolsheviks implemented policies of “War Communism,” requisitioning grain from peasants at gunpoint and executing those who resisted.

The Don and Kuban Cossack republics allied with White Russian forces against the Bolsheviks, but this alliance proved problematic as White leaders favored a “one and indivisible Russia” and opposed Cossack autonomy. When the White armies collapsed in 1920, the Cossack territories fell to Bolshevik control, ending their brief independence.

By 1921, the multiple conflicts had resulted in a divided Ukraine. Eastern and central Ukraine came under Soviet control, with the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic established as a founding member of the USSR in 1922. Western Ukrainian territories were incorporated into Poland, Romania, and Czechoslovakia. The Ukrainian national movement had failed to secure independence, but it had established Ukraine as a political concept that could not be easily dismissed.

Soviet Policy in Ukraine: From Ukrainization to Terror

The early Soviet period presented a paradox for Ukraine. While politically subordinated to Moscow, the 1920s saw an official policy of “Ukrainization” – promoting Ukrainian language, culture, and education as part of the Soviet nationalities policy. Ukrainian cultural and intellectual life flourished briefly, with writers, artists, and scholars creating what became known as the “Executed Renaissance.”

This relatively liberal approach was driven by pragmatic concerns. The Bolsheviks recognized that Ukrainian national sentiment had played a significant role in resistance to their rule. By granting cultural concessions while maintaining political control, they hoped to pacify Ukrainian society. Additionally, Ukrainization aimed to spread Communist ideology to the predominantly Ukrainian-speaking rural population.

However, by the late 1920s, as Joseph Stalin consolidated power in Moscow, Soviet policy shifted dramatically. Stalin viewed Ukrainian national consciousness with suspicion, particularly as it gained strength among Ukrainian Communists. The Ukrainian Communist leadership, including figures like Mykola Skrypnyk and Oleksandr Shumsky, advocated for greater Ukrainian autonomy within the Soviet system, a position Stalin regarded as dangerously nationalistic.

Stalin’s answer to Ukrainian assertions of national identity was brutal. Beginning in 1929, he launched a campaign against “national deviationists” in the Ukrainian Communist Party. This was followed by a broader assault on Ukrainian intellectuals, with thousands of writers, artists, scholars, and cultural figures arrested, executed, or sent to labor camps. The Ukrainian Autocephalous Orthodox Church, which had asserted independence from the Moscow Patriarchate, was liquidated, its clergy arrested or killed.

The Holodomor: Genocide by Starvation

The most devastating blow to Ukraine came with the artificial famine of 1932-33, known in Ukrainian as the Holodomor (“death by hunger”). This catastrophe resulted from Stalin’s policies of forced collectivization of agriculture, combined with punitive grain procurement quotas specifically targeted at Ukraine.

The Soviet regime requisitioned grain and other foodstuffs from Ukrainian villages at impossible levels, leaving peasants with nothing to eat. When resistance occurred, entire villages were blacklisted, with residents forbidden to leave in search of food. NKVD (secret police) units and Communist Party activists sealed Ukraine’s borders to prevent starving peasants from fleeing to other regions of the USSR where food was available. Those caught trying to flee or hiding food were executed or sent to labor camps.

The result was apocalyptic. At the height of the famine in spring 1933, an estimated 25,000 people died daily. Parents watched helplessly as their children starved to death. Cases of cannibalism were reported. In total, between 3.5 and 5 million Ukrainians perished during the Holodomor.

Scholars continue to debate whether the Holodomor constitutes genocide, but evidence increasingly supports this classification. Stalin specifically targeted Ukraine to crush peasant resistance to collectivization and to destroy Ukrainian national identity, which he viewed as a threat to Soviet unity. The famine coincided with the arrest and execution of thousands of Ukrainian cultural and political figures accused of “bourgeois nationalism.”

In the aftermath, the depopulated Ukrainian countryside was resettled with non-Ukrainian migrants, particularly in eastern regions, permanently altering the demographic composition of these areas. The trauma of the Holodomor was compounded by Soviet prohibition of any public acknowledgment of the famine, which was denied and covered up until the final years of the USSR.

The Decossackization Campaign: Cultural Genocide Against the Cossacks

While Ukraine suffered under Stalin’s brutal policies, the Cossack communities of the Don, Kuban, and other regions faced their own devastating persecution. Following the Bolshevik victory in the Civil War, Soviet authorities implemented a policy known as “Decossackization” (Raskazachivaniye), targeting Cossacks as a distinct social and cultural group.

The Bolsheviks viewed the Cossacks, with their military traditions and strong group identity, as inherently counter-revolutionary. On January 24, 1919, the Central Committee issued a secret directive calling for “the complete, rapid, decisive extermination of the Cossacks as a distinct economic group, the destruction of their economic foundations, the physical elimination of Cossack officials and officers, and generally of all Cossack leaders.”

What followed was a systematic campaign of terror. Thousands of Cossacks were executed without trial, often in public to intimidate others. Cossack villages were burned, and their land redistributed to non-Cossack peasants. Deportations sent entire Cossack communities to labor camps in Siberia and the Far North, where many died from cold, starvation, and exhaustion.

The Kuban Cossacks, many of whom identified culturally and linguistically as Ukrainian, faced particularly severe repression. In the early 1930s, the Kuban region experienced famine conditions similar to Ukraine as Soviet authorities implemented the same policies of grain requisitioning and blacklisting of villages. Simultaneously, the use of the Ukrainian language, which had been common in Kuban schools and publications, was prohibited, and Ukrainian-language schools were closed.

By the mid-1930s, Cossack identity had been effectively criminalized. Traditional Cossack customs, clothing, and cultural expressions were banned. Cossack family histories became dangerous secrets to be hidden, as having Cossack ancestry could lead to discrimination, arrest, or worse. The campaign constituted one of history’s clearest examples of cultural genocide – the deliberate destruction of a people’s cultural identity.

Western Ukraine: Different Rulers, Similar Repression

While Soviet Ukraine experienced terror and famine, Ukrainians in territories annexed by Poland, Romania, and Czechoslovakia faced their own struggles. The most significant Ukrainian population lived under Polish rule in eastern Galicia and Volhynia.

The Polish government, dominated by nationalist forces, viewed its Ukrainian minority with suspicion. Despite initial promises of autonomy, Poland implemented policies of assimilation and colonization. Ukrainian-language education was restricted, Ukrainian civil servants were dismissed, and Polish settlers were encouraged to move into predominantly Ukrainian areas.

In response, Ukrainian political life in Poland diversified, ranging from moderate parties working within the Polish system to radical underground organizations. The most significant of these was the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN), founded in 1929, which advocated armed resistance against Polish rule. The OUN conducted sabotage operations and political assassinations, which prompted harsh Polish counter-measures, including mass arrests and the notorious “pacification” campaign of 1930, when Polish troops and police brutalized Ukrainian villages suspected of supporting the OUN.

Romanian rule in Bukovina and Bessarabia was even harsher, with aggressive Romanianization policies banning Ukrainian cultural and educational institutions entirely. Only in Czechoslovak-controlled Transcarpathia did Ukrainians experience relatively liberal treatment, with cultural and linguistic rights protected and a degree of political autonomy granted.

The Road to World War II: Ukraine as Pawn in Great Power Politics

As Europe moved toward another world war in the late 1930s, Ukrainian territories again became pawns in great power politics. The 1938 Munich Agreement resulted in Nazi Germany’s annexation of Czechoslovakia’s Sudetenland, followed by the dismemberment of the entire Czechoslovak state in March 1939. Transcarpathia briefly declared independence as Carpatho-Ukraine, only to be immediately invaded and annexed by Hungary, a Nazi ally.

The most consequential development came with the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact of August 1939, in which Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union agreed to divide Eastern Europe between them. Following the German invasion of Poland on September 1, 1939, which initiated World War II, the Soviet Union invaded eastern Poland on September 17, annexing territories with large Ukrainian populations.

Stalin immediately set about integrating these newly acquired western Ukrainian territories into the Soviet system. The Soviet secret police arrested thousands of Ukrainian political and cultural leaders, as well as Polish officials and military officers. Religious institutions were suppressed, private businesses nationalized, and collectivization of agriculture initiated. Between 1939 and 1941, an estimated 400,000 people were deported from western Ukraine to Siberia and Central Asia.

For their part, the Cossack communities had been so thoroughly crushed by a decade of Soviet repression that they could offer little organized resistance. However, Stalin remained suspicious of Cossack loyalties, and many Cossacks were preemptively arrested or deported as potential “enemies of the people” as war approached.

Conclusion: The Legacy of Oppression and Resistance

The period from World War I through the interwar years transformed Ukraine and the broader region in ways that continue to shape its politics and identity today. The brief flowering of Ukrainian statehood during 1917-1921, though ultimately unsuccessful, established a historical precedent for independence that would be realized seventy years later. Similarly, the brutal repression of the Cossacks nearly extinguished their distinct identity but created martyrs and memories that would fuel later revival movements.

Stalin’s campaign of terror against Ukraine – the executions of the intelligentsia, the Holodomor, the destruction of cultural institutions – represented an attempt to solve the “Ukrainian question” once and for all by breaking the nation’s spirit. That Ukraine nevertheless maintained its national identity through these horrors testifies to extraordinary resilience. However, these events also left deep scars on Ukrainian society, creating regional divisions and historical traumas that continue to resonate.

For the Cossack communities, the Decossackization campaign and subsequent repression nearly succeeded in destroying their distinct identity. Traditional Cossack culture was driven underground or into emigration, with many Cossack traditions preserved only by diaspora communities in Europe and North America. Within the Soviet Union, being identified as a Cossack became dangerous, leading many families to hide their heritage.

As World War II approached, both Ukrainians and Cossacks had experienced the brutality of Soviet rule and the indifference of Western powers to their fate. This would shape their complex and often desperate choices during the coming conflict, as they sought to navigate between the twin totalitarian systems of Stalinism and Nazism – a choice that has sometimes been described as deciding “between the hammer and the anvil.”

Understanding this forgotten chapter of history illuminates not only the past but also contemporary conflicts. The current war in Ukraine, Russia’s annexation of Crimea, and tensions over Cossack identity in southern Russia all have roots in these historical experiences. By recognizing how the aspirations of Ukrainians, Cossacks, and other peoples of the region were crushed between competing empires and ideologies, we gain insight into the deep historical currents that continue to shape this contested borderland.

References and Further Reading

Applebaum, A. (2017). Red Famine: Stalin’s War on Ukraine. Doubleday.

Conquest, R. (1986). The Harvest of Sorrow: Soviet Collectivization and the Terror-Famine. Oxford University Press.

Holquist, P. (2002). Making War, Forging Revolution: Russia’s Continuum of Crisis, 1914-1921. Harvard University Press.

Hunczak, T. (Ed.). (1977). The Ukraine, 1917-1921: A Study in Revolution. Harvard Ukrainian Research Institute.

Liber, G. (2016). Total Wars and the Making of Modern Ukraine, 1914-1954. University of Toronto Press.

Magocsi, P. R. (2010). A History of Ukraine: The Land and Its Peoples (2nd ed.). University of Toronto Press.

Martin, T. (2001). The Affirmative Action Empire: Nations and Nationalism in the Soviet Union, 1923-1939. Cornell University Press.

Plokhy, S. (2015). The Gates of Europe: A History of Ukraine. Basic Books.

Reshetar, J. S. (1952). The Ukrainian Revolution, 1917-1920: A Study in Nationalism. Princeton University Press.

Rudnytsky, I. L. (1987). Essays in Modern Ukrainian History. Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies.

Senn, A. E. (1971). The Russian Revolution in Switzerland, 1914-1917. University of Wisconsin Press.

Shane, M. P. (2005). The Affirmative Action Empire: Nations and Nationalism in the Soviet Union, 1923-1939. Harvard University Press.

Snyder, T. (2010). Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin. Basic Books.

Solonari, V. (2009). Purifying the Nation: Population Exchange and Ethnic Cleansing in Nazi-Allied Romania. Woodrow Wilson Center Press.

Subtelny, O. (2009). Ukraine: A History (4th ed.). University of Toronto Press.

Yekelchyk, S. (2007). Ukraine: Birth of a Modern Nation. Oxford University Press.

You must be logged in to post a comment.