This Part 2 of 2 blog posts discussing the political and military significance of D-Day and the Big3. You can read Part 1 here.

History pivots on moments of decision, and few decisions were more consequential than Franklin Roosevelt’s rejection of Winston Churchill’s Mediterranean strategy in favor of the cross-Channel invasion of France. But what if the American president had instead embraced his British ally’s vision of striking through Italy and the Balkans? What if the Tehran Conference of November 1943 had ended not in unity, but in strategic deadlock, with Stalin, Churchill, and Roosevelt unable to agree on a coordinated approach to defeating Nazi Germany?

This alternate history reveals how dramatically different choices might have reshaped not only the war’s conclusion, but the entire post-war world order.

The Fracture at Tehran: When the Big Three Couldn’t Agree

In our timeline, Stalin’s insistence on a second front in France aligned with American strategic thinking, isolating Churchill’s Mediterranean preferences. But imagine if Roosevelt, swayed by mounting casualties in the Pacific and growing skepticism about Soviet intentions, had instead sided with Churchill’s argument that the “soft underbelly of Europe” offered the most promising route to victory.

At this alternate Tehran Conference, Stalin would have found himself facing a united Anglo-American front determined to pursue a strategy he viewed as deliberately designed to limit Soviet influence in post-war Europe. The Soviet leader, already suspicious of Western motives, would have seen Churchill’s Balkan obsession as a transparent attempt to beat the Red Army to Central Europe and establish Western influence in what he considered the Soviet sphere.

The conference would have ended in acrimony, with Stalin demanding immediate action in France while Churchill and Roosevelt insisted on Mediterranean operations. Unable to coordinate their strategies, the three leaders would have returned to their capitals to pursue parallel but uncoordinated campaigns, fundamentally altering the dynamic of the Grand Alliance.

The Mediterranean Gambit: Successes and Catastrophes

With Roosevelt’s support, Churchill’s Mediterranean strategy would have received the full weight of American industrial and military might. Instead of the relatively modest Italian campaign that historically bogged down in brutal mountain warfare, this alternate timeline would have seen a massive Allied commitment to the region. American divisions that historically prepared for D-Day would instead have poured into Italy, while substantial resources would have flowed to support Tito’s partisans in Yugoslavia and other Balkan resistance movements.

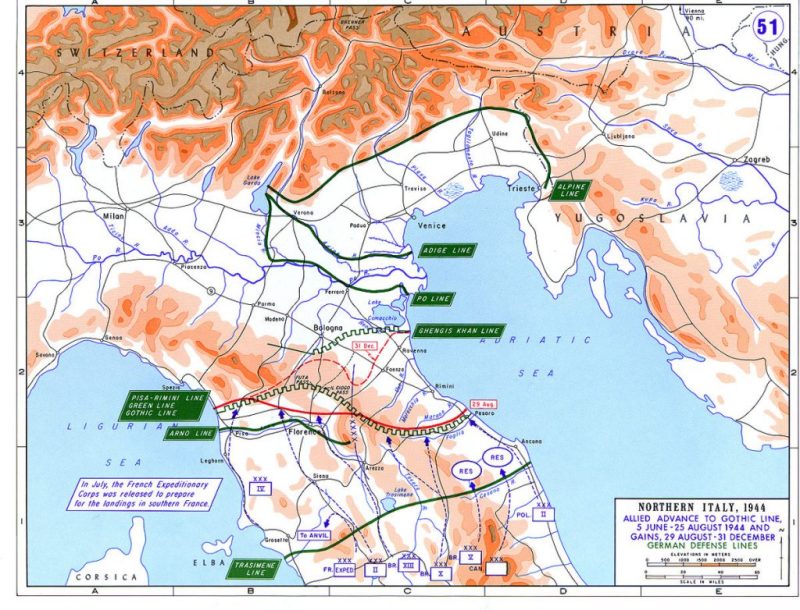

The initial successes would have been dramatic. Rome would have fallen months earlier, and the Gothic Line would have crumbled under the weight of massive Allied superiority. By spring 1944, Allied forces would have been pushing through the Ljubljana Gap toward Austria, while simultaneously supporting a major uprising in Yugoslavia that liberated much of the country from German control.

Churchill’s vision of linking up with Soviet forces somewhere in Central Europe would have seemed tantalizingly close to reality. American and British divisions might have reached Vienna by summer 1944, potentially changing the entire dynamic of the war’s final phase. The psychological impact on German morale would have been devastating, as the Reich faced the prospect of Allied armies approaching from both south and east.

Yet this success would have come at an enormous cost. The delay in opening the Second Front would have prolonged the war significantly. German forces freed from defending the Atlantic Wall could have been redeployed to the Eastern Front, potentially slowing Soviet advances and resulting in millions of additional casualties. The Holocaust would have continued for months longer, with catastrophic consequences for Europe’s Jewish population.

Stalin’s Separate Peace: The Alliance Crumbles

Faced with an Anglo-American strategy he viewed as aimed directly at limiting Soviet post-war influence, Stalin would have had powerful incentives to consider alternatives. With no Second Front to relieve pressure on the Eastern Front, and watching Western forces advance toward the heart of Europe through the Balkans, the Soviet leader might have calculated that a separate peace with Germany offered better prospects than continued alliance with increasingly untrustworthy partners.

Such a peace would not have meant Soviet surrender—Stalin was too committed to defeating fascism and too aware of Hitler’s fundamental hostility to communist ideology. Instead, it might have taken the form of a temporary armistice that allowed both sides to consolidate their positions while focusing on other threats. Hitler, facing the prospect of Allied armies in Austria and potential uprisings throughout the Balkans, might have been willing to accept such an arrangement.

The psychological impact of this development on the Western Allies would have been devastating. Public opinion in both Britain and America, already war-weary after years of conflict, would have been shattered by the apparent collapse of the Grand Alliance. Roosevelt would have faced a political crisis that could have threatened his chances in the 1944 election, while Churchill would have confronted challenges to his leadership from those who had warned against trusting Stalin.

The 1944 Election in Crisis

Roosevelt’s decision to pursue the Mediterranean strategy would have fundamentally altered the dynamics of his re-election campaign. Instead of celebrating the liberation of Paris and the rapid advance across France, Americans would have been confronting the possibility of a separate Soviet-German peace and the prospect of a prolonged war with uncertain outcomes.

Thomas Dewey would have seized on this strategic confusion as evidence of Roosevelt’s failed leadership. The Republican candidate would have argued that the president’s decision to follow Churchill’s lead had endangered American interests and prolonged the war unnecessarily. The fact that American boys were dying in Italian mountain passes while Stalin negotiated with Hitler would have provided powerful ammunition for Roosevelt’s critics.

The president would have faced the difficult task of explaining to the American people why their forces were fighting in the Balkans rather than France, particularly if the promised quick victory had failed to materialize. His famous political skills would have been tested as never before, as he attempted to maintain support for a strategy that appeared to have backfired spectacularly.

The election results would likely have been much closer than in our timeline, with Roosevelt’s margin of victory significantly reduced or possibly facing defeat. A Dewey victory would have introduced additional uncertainty into an already chaotic strategic situation, as the new president would have had to decide whether to continue Roosevelt’s Mediterranean commitment or pivot to a different approach.

A Different Cold War: Western Europe vs. Eastern Empire

The long-term consequences of this alternate timeline would have been profound. A successful Allied advance through the Balkans might have resulted in Western occupation of much of Central Europe, fundamentally altering the post-war balance of power. Instead of the Iron Curtain falling across the heart of Europe, it might have been drawn much further east, with countries like Czechoslovakia, Hungary, and Poland potentially falling under Western rather than Soviet influence.

Yet this apparent Western success would have come at the cost of a much more hostile relationship with the Soviet Union. Stalin’s experience of what he would have seen as Western betrayal would have convinced him that peaceful coexistence was impossible. The Cold War would have begun not in 1947 but in 1944, with much higher tensions and possibly a greater risk of direct military confrontation.

The nuclear age would have arrived in a world already divided into hostile camps, with both sides having had additional time to prepare for confrontation. The Soviet Union, having maintained larger forces in Eastern Europe due to the continued German threat, would have been better positioned for conventional warfare, while the United States would have faced the challenge of maintaining extended supply lines to forces deep in Central Europe.

The Asian Consequences: Japan’s Extended War

The commitment of additional American resources to the Mediterranean would have had profound implications for the Pacific War. The invasion of the Philippines might have been delayed by months, while the planned invasion of Japan would have faced severe resource constraints. The atomic bomb, when finally deployed, might have faced a Japan that had additional time to prepare its defenses and steel its population for the final battle.

MacArthur’s island-hopping campaign would have proceeded more slowly, with fewer resources and facing a Japanese military that had more time to fortify its positions. The human cost of ending the Pacific War would likely have been much higher, both for Allied forces and for Japanese civilians caught in prolonged fighting.

China’s civil war would have unfolded differently as well, with Communist forces potentially gaining additional advantages from prolonged conflict and delayed American attention to Asian affairs. The eventual victory of Mao’s forces might have come sooner and been more complete, fundamentally altering the balance of power in post-war Asia.

Reflections on Roads Not Taken

This alternate history reveals how interconnected the strategic decisions of 1943-1944 truly were. Churchill’s Mediterranean strategy, while offering potential advantages in terms of post-war European politics, would have carried enormous risks and costs. The delay in opening the Second Front might have prolonged the war significantly, while the breakdown in Allied cooperation could have led to outcomes far worse than anything that occurred in our timeline.

The failure to reach agreement at Tehran would have demonstrated the fragility of the Grand Alliance and the extent to which personal relationships between leaders shaped global strategy. Roosevelt’s ability to work with both Churchill and Stalin, despite their fundamental disagreements, proved crucial to maintaining the unity necessary for victory.

Perhaps most importantly, this alternate timeline illustrates how military strategy and political outcomes are inextricably linked. Churchill’s preference for Mediterranean operations was never purely military—it reflected his deep understanding of how wartime positions would shape post-war politics. Roosevelt’s rejection of this strategy, while potentially costly in terms of post-war Soviet influence, may have been necessary to maintain the alliance that ultimately defeated Nazi Germany.

The road not taken reminds us that the Allied victory we celebrate today was not inevitable, but rather the result of difficult decisions made under enormous pressure by leaders who could only guess at the long-term consequences of their choices. In imagining how different these choices might have been, we gain a deeper appreciation for both the successes and the costs of the path that history actually took.

Suggested Reading

For those interested in exploring these counterfactual scenarios and the actual strategic debates that shaped World War II, consider these essential works:

The Ascent to Power by David L. Roll provides crucial insight into Roosevelt’s decision-making process and his navigation of the competing pressures from Churchill and Stalin during this critical period.

Stalin: Waiting for Hitler, 1929-1941 by Stephen Kotkin provide unparalleled insight into Soviet strategic thinking and Stalin’s complex relationship with his Western allies.

Masters and Commanders by Andrew Roberts examines the strategic debates between Churchill, Roosevelt, and their military advisors, showing how personality and politics shaped military strategy.

What If?: The World’s Foremost Military Historians Imagine What Might Have Been edited by Robert Cowley includes several essays exploring alternate outcomes of World War II strategic decisions.

These works together provide the foundation for understanding both what happened and what might have been during this crucial period of modern history.

This is part of a series of blog posts looking at different aspects of WW1 and WW2 that do not always get mentioned in the classroom. To read more of these stories follow the link 20th Century.

You must be logged in to post a comment.