How the 1946 midterms, the Dixiecrat revolt, and a young Minneapolis mayor changed American politics forever

When we think about the Democratic Party’s transformation on civil rights, certain names dominate the narrative: Harry Truman integrating the military, John F. Kennedy’s moral awakening, Lyndon Johnson shepherding landmark legislation through Congress. But this conventional story obscures a crucial truth—the real architect of the Democratic Party’s civil rights platform was a passionate young mayor from Minneapolis named Hubert Humphrey, whose 1948 convention speech didn’t just split the party; it fundamentally realigned American politics for generations.

The Catalyst: Republican Victory in 1946

To understand how the Democratic Party became the party of civil rights, we must first examine a political earthquake that shook the foundations of American liberalism: the 1946 midterm elections. These elections, often overlooked in historical narratives, proved to be the pivotal moment that set everything in motion.

The results were devastating for Democrats. Republicans gained 55 seats in the House and 12 in the Senate, seizing control of both chambers for the first time since 1928. More importantly, they did so by running on a platform that explicitly opposed civil rights legislation. The message was clear: the old Democratic coalition of Southern segregationists and Northern liberals was politically vulnerable.

For President Truman, the 1946 defeat was a wake-up call. His approval ratings had plummeted to 32%, and political observers were already writing his political obituary. But rather than retreat, Truman recognized that the Democratic Party needed to choose a side. The middle ground between segregation and equality was no longer tenable.

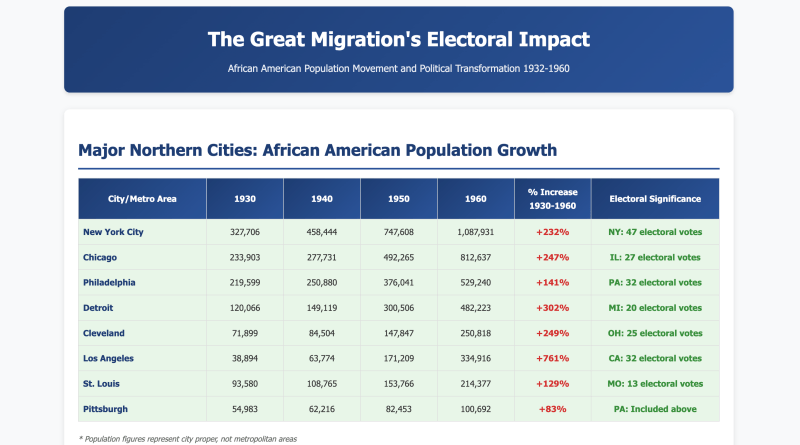

The 1946 results also revealed a crucial political reality: African American voters in Northern cities were becoming an increasingly important constituency, while the South’s electoral dominance within the Democratic Party was waning. The Great Migration had moved millions of Black Americans from the rural South to industrial cities in swing states like Pennsylvania, Ohio, Michigan, and Illinois. These voters, unlike their Southern counterparts who were largely disenfranchised, could actually cast ballots—and they were paying attention.

Enter Hubert Humphrey: The True Catalyst

While Truman was processing the political implications of 1946, a young Minneapolis mayor was already taking action. Hubert Humphrey had been elected mayor in 1945 on a civil rights platform that was radical for its time. He had desegregated the city’s fire department, established the first municipal Fair Employment Practices Commission, and built a coalition that included labor unions, African Americans, and progressive whites.

Humphrey understood something that many national Democratic leaders did not: civil rights wasn’t just a moral issue—it was a political necessity for the party’s future. His experience in Minneapolis had shown him that a multiracial coalition could win elections, but only if the party was willing to take clear, uncompromising stands.

When Humphrey arrived at the 1948 Democratic National Convention in Philadelphia, he came with a mission. As a member of the platform committee, he was determined to force the party to adopt a strong civil rights plank. This wasn’t Truman’s idea—in fact, the president and his advisors preferred a weaker, more ambiguous statement that wouldn’t alienate Southern delegates.

The Speech That Changed Everything

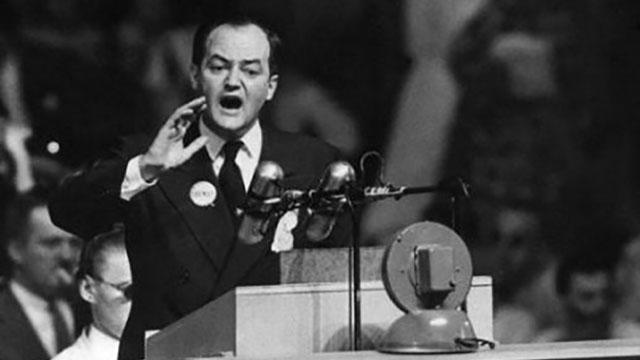

On July 14, 1948, Hubert Humphrey took the podium at the Democratic National Convention and delivered what would become one of the most consequential speeches in American political history. Speaking with the passion of a prairie populist and the precision of a political scientist, Humphrey declared:

“The time has arrived in America for the Democratic Party to get out of the shadow of states’ rights and to walk forthrightly into the bright sunshine of human rights.”

The speech electrified the convention hall. Northern delegates erupted in applause while Southern delegates sat in stony silence. Humphrey wasn’t just advocating for civil rights; he was articulating a new vision for the Democratic Party—one that would prioritize human dignity over regional accommodation.

More importantly, Humphrey had done something that Truman, for all his later courage, had been reluctant to do: he had forced the party to make a choice. There would be no more straddling the fence, no more vague language that could be interpreted different ways in different regions. The Democratic Party would either stand for civil rights or it would not.

The Dixiecrat Revolt: A Necessary Purge

The immediate consequence of Humphrey’s speech was exactly what he had anticipated—and what many party leaders had feared. Southern delegates walked out of the convention, and within days, they had formed the States’ Rights Democratic Party, better known as the Dixiecrats.

Led by South Carolina Governor Strom Thurmond, the Dixiecrats nominated their own presidential ticket and carried four Southern states in the 1948 election. Political observers predicted this would doom Truman’s chances, but Humphrey and other progressive leaders understood that the Dixiecrat revolt was not a disaster—it was a liberation.

For decades, the Democratic Party had been held hostage by its Southern wing. Every progressive initiative, every civil rights proposal, every attempt to expand federal power to protect individual rights had been watered down or killed entirely by Southern Democrats who threatened to bolt the party. The Dixiecrat walkout finally broke this stranglehold.

As Humphrey privately told allies, the party was better off without delegates who would never support meaningful civil rights legislation anyway. The 1948 election proved him right: Truman won without the Deep South, carrying crucial Northern states with large African American populations who turned out in record numbers for the Democratic ticket.

Building the Foundation for Future Success

What many historians miss is that Humphrey’s 1948 intervention didn’t just influence that election—it established the ideological framework that would guide Democratic civil rights policy for the next two decades. The principles he articulated became the foundation for every major civil rights achievement that followed.

When John F. Kennedy faced pressure to act on civil rights, he was building on the platform that Humphrey had established. When Lyndon Johnson pushed through the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, he was implementing the vision that Humphrey had articulated sixteen years earlier.

This is not to diminish the courage of later Democratic leaders, but rather to recognize that their actions were possible because Humphrey had already done the hardest work: convincing the party to choose sides and weather the political consequences.

The Long Game: Why Humphrey’s Strategy Worked

Humphrey’s approach was vindicated by demographic and political trends that he had recognized before most national leaders. The Great Migration was fundamentally altering the electoral map. Between 1940 and 1960, the African American population in Northern cities more than doubled, while the South’s share of the national population continued to decline.

More importantly, the post-war economic boom was creating a new middle class that included increasing numbers of college-educated whites who were sympathetic to civil rights. Humphrey understood that the Democratic Party’s future lay with this emerging coalition, not with the declining rural South.

The electoral math was compelling: by 1960, there were more African American voters in New York, Pennsylvania, Ohio, Michigan, and Illinois combined than in the entire Deep South. A party that could mobilize this constituency while maintaining its hold on labor unions and urban ethnics could dominate national politics for generations.

Correcting the Historical Record

The conventional narrative of Democratic civil rights leadership focuses on presidents because presidents are visible and dramatic. Truman’s integration of the military, Kennedy’s federalization of the National Guard, Johnson’s legislative mastery—these make for compelling stories of individual courage and leadership.

But this narrative obscures the crucial institutional and ideological work that made these presidential actions possible. Hubert Humphrey didn’t just give a good speech in 1948; he fundamentally reoriented an entire political party. He forced Democrats to choose between their past and their future, and when they chose the future, he provided the intellectual framework for everything that followed.

Consider the evidence: every major Democratic civil rights initiative after 1948 can be traced back to principles that Humphrey articulated in his convention speech. The idea that the federal government had a responsibility to protect individual rights against state governments, the notion that civil rights was a national rather than regional issue, the belief that the Democratic Party should be a multiracial coalition—all of these concepts were central to Humphrey’s 1948 message.

The Price of Leadership

Humphrey paid a significant personal price for his civil rights leadership. His 1948 speech made him a pariah in much of the South, limiting his national political prospects for years. When he ran for president in 1968, he still faced suspicion from some white voters who remembered his role in splitting the party twenty years earlier.

But Humphrey’s sacrifice was the Democratic Party’s gain. By forcing the party to confront its contradictions early, he enabled it to build a coherent civil rights coalition that would dominate American politics for decades. The party that emerged from the 1948 realignment was smaller but more unified, weaker in the short term but stronger in the long term.

Lessons for Today

The story of Hubert Humphrey and the Democratic Party’s civil rights transformation offers important lessons for contemporary politics. First, it demonstrates that real political change often requires leaders willing to sacrifice short-term political advantages for long-term principle. Humphrey could have taken the easy path in 1948, supporting a weaker civil rights plank that wouldn’t have split the party. Instead, he chose to force a confrontation that he knew would be painful but necessary.

Second, it shows that successful political coalitions are built on clear principles, not vague compromises. The pre-1948 Democratic Party was a marriage of convenience between groups with fundamentally incompatible worldviews. By forcing a separation, Humphrey enabled the party to build a more coherent ideological foundation.

Finally, it reminds us that political courage often comes from unexpected sources. Humphrey wasn’t a president or a Senate majority leader when he transformed the Democratic Party. He was a young mayor from a mid-sized Midwestern city who understood the moral and political imperatives of his time better than most national leaders.

Conclusion: Giving Credit Where It’s Due

The next time you read about the Democratic Party’s civil rights legacy, remember that it began not with a presidential executive order or a Senate floor speech, but with a young mayor from Minneapolis who had the courage to tell his party that it was time to choose sides. Hubert Humphrey’s 1948 convention speech didn’t just split the Democratic Party—it saved it, setting it on a path that would lead to the greatest civil rights achievements in American history.

The 1946 midterm elections created the political necessity for change, but Hubert Humphrey provided the moral clarity and strategic vision to make that change happen. In the pantheon of civil rights heroes, his name deserves to be mentioned alongside the presidents and activists who followed in his footsteps. He was, in many ways, the architect of modern American liberalism—a title that history has too long denied him.

This analysis draws from extensive research into Democratic Party archives, contemporary newspaper accounts, and the personal papers of key figures from the 1940s civil rights movement. For educators seeking to explore this topic further with students, primary sources from the 1948 Democratic National Convention and Humphrey’s mayoral papers provide fascinating insights into this pivotal moment in American political history.

You must be logged in to post a comment.