In the depths of the Great Depression, as Franklin Delano Roosevelt pushed forward his New Deal programs, a group of wealthy industrialists allegedly hatched an audacious plan: recruit a decorated Marine general to lead a fascist-style coup against the U.S. government. What became known as the Business Plot—or the Wall Street Putsch—represents one of the most extraordinary political conspiracies in American history, even if its full scope remains debated to this day.

The Approach to a Reluctant General

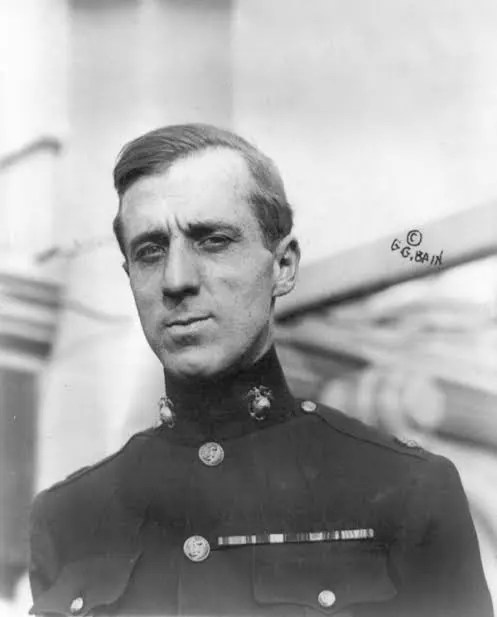

Major General Smedley Darlington Butler was an unlikely target for conspirators seeking to overthrow American democracy. A two-time Medal of Honor recipient, Butler was the most decorated Marine of his era, having spent 33 years in uniform fighting in campaigns from the Philippines to China to Central America. By 1933, however, Butler had become an outspoken critic of American imperialism and corporate influence over foreign policy. His 1935 book would famously declare: “I spent most of my time being a high-class muscle-man for Big Business, for Wall Street and for the Bankers.”

Despite—or perhaps because of—his anti-establishment credentials and popularity among veterans, Butler claimed he was approached in the summer and fall of 1933 by a series of intermediaries representing wealthy businessmen. The principal contact was Gerald C. MacGuire, a bond salesman who had served under Butler during World War I and now worked for Grayson M.-P. Murphy & Co., a prominent Wall Street firm.

According to Butler’s later testimony, MacGuire initially approached him about speaking at an American Legion convention to advocate for maintaining the gold standard—a position that would counter Roosevelt’s monetary policies. Butler refused. But MacGuire persisted, eventually revealing a far more ambitious scheme.

The Alleged Plot Unfolds

Butler testified that MacGuire and his associates proposed that he lead a march of 500,000 veterans on Washington, D.C., ostensibly to pressure Roosevelt to create a new cabinet position—Secretary of General Affairs—who would handle the “details” of running the country while the president became a ceremonial figurehead. Butler would command this private army of veterans, modeled after the fascist leagues that had recently helped bring authoritarian governments to power in Europe, particularly France’s Croix de Feu.

The conspirators reportedly promised substantial financial backing. MacGuire claimed to represent wealthy industrialists who were prepared to spend up to $300 million to fund the operation. He spoke of having already secured commitments from major business leaders and even showed Butler bank deposit slips that he claimed proved the financial backing was real.

Butler was alarmed but played along to gather more information. In his testimony, he recounted MacGuire telling him: “We need a fascist government in this country to save the nation from the Communists who want to tear it down and wreck all that we have built in America. The only men who have the patriotism to do it are the soldiers, and Smedley Butler is the ideal leader.”

Taking It to Congress

Rather than participate, Butler went public. He first approached newspaper reporters, including Paul Comly French of the Philadelphia Record and the New York Post, who conducted their own investigation. French actually met with MacGuire independently and corroborated key elements of Butler’s account, including references to wealthy backers and plans for a veterans’ organization.

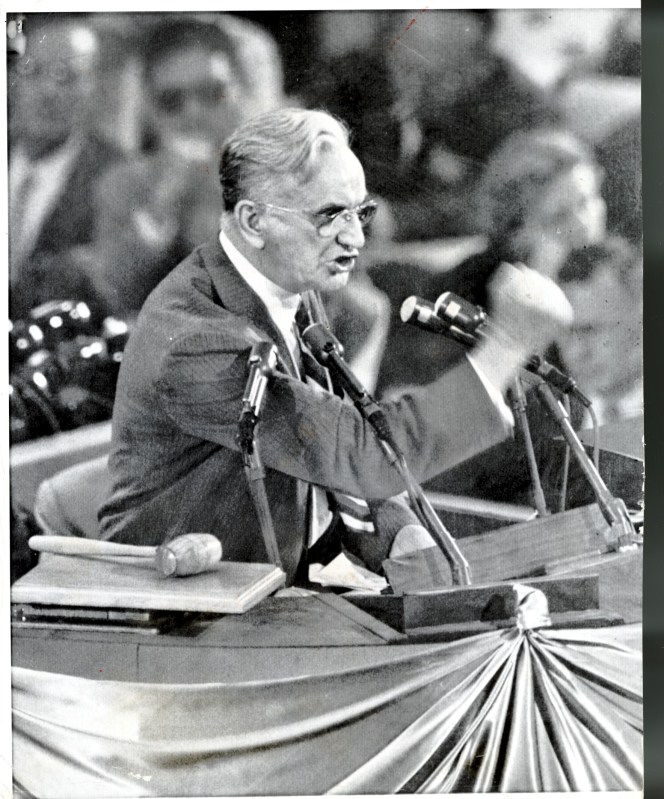

In November 1934, Butler testified before the House Committee on Un-American Activities, then chaired by Representatives John W. McCormack of Massachusetts and Samuel Dickstein of New York. The committee’s investigation became known as the McCormack-Dickstein Committee hearings.

Butler’s testimony was dramatic and detailed. He named names and provided specifics about his conversations with MacGuire, including MacGuire’s claim that “We have three million dollars to start with on the line and we can get three million more if we need it.” Butler also testified that MacGuire had told him the plotters had secured the support of the American Legion’s commander and had been studying European fascist movements for tactics.

The committee heard from other witnesses as well. Paul French testified about his independent conversations with MacGuire, stating: “He said the time to have done it was when the bank moratorium was on. That would have been an ideal time to have started a veterans’ organization to have taken over the Government.”

The Committee’s Findings

The McCormack-Dickstein Committee took the allegations seriously. In its final report, issued in February 1935, the committee concluded: “In the last few weeks of the committee’s official life it received evidence showing that certain persons had made an attempt to establish a fascist organization in this country… There is no question that these attempts were discussed, were planned, and might have been placed in execution when and if the financial backers deemed it expedient.”

The committee’s report specifically stated: “This committee received evidence from Major General Smedley D. Butler (retired), twice decorated by the Congress of the United States. He testified before the committee as to conversations with one Gerald C. MacGuire in which the latter is alleged to have suggested the formation of a fascist army under the leadership of General Butler.”

Regarding MacGuire’s testimony, the committee noted that while he denied the more elaborate aspects of the plot, he had admitted to making a European trip to study veterans’ organizations, and his explanations were often “evasive” and contradictory.

The committee concluded: “Evidence was obtained showing that certain persons had made an attempt to establish a fascist organization in this country. No evidence was presented and this committee had none to show a connection between this effort and any fascist activity of any European country. This committee asserts that any efforts based on lines as suggested in the foregoing and leading off in any direction, will be regarded by the committee as being highly dangerous, un-American, and can have no place in this country if our form of government is to be preserved.”

Why No Prosecutions?

Despite the committee’s findings that a plot had indeed been discussed and planned, no criminal charges were ever filed against any of the alleged conspirators. This remains one of the most perplexing aspects of the affair. Several factors likely contributed to this outcome:

Lack of Concrete Action: While the committee found evidence of discussions and planning, there was no evidence that any actual steps toward executing a coup had been taken. The conspiracy had not progressed beyond conversation and preliminary organization. In American law, discussing illegal acts is not necessarily criminal; there must typically be evidence of concrete steps toward committing those acts.

Powerful Connections: The men allegedly involved represented some of America’s most influential families and corporations. Though never directly named in official testimony, Butler claimed the conspiracy involved members of the Morgan and DuPont families, as well as officials from major corporations like Goodyear, Standard Oil, and General Motors. Robert Sterling Clark, an heir to the Singer sewing machine fortune who had funded MacGuire’s European trip, was among those implicated. Prosecuting such figures would have been politically explosive and legally challenging, particularly with the limited evidence available.

Political Calculation: The Roosevelt administration was already facing fierce opposition from business interests over the New Deal. Some historians have suggested that FDR may have calculated that exposing and prosecuting such a plot would create more problems than it solved, potentially destabilizing confidence in American institutions during an already precarious economic period. The president never publicly commented on the affair.

Butler’s Credibility Questions: While Butler was a genuine American hero, some questioned whether he might have misinterpreted or exaggerated what were perhaps more innocuous approaches by eccentric businessmen. The New York Times dismissed the allegations as a “gigantic hoax,” though this stance has been challenged by later historians who have found corroborating evidence. The ambiguity around Butler’s interpretation of events made prosecution more difficult.

Limited Committee Power: The McCormack-Dickstein Committee was tasked with investigating un-American activities, but it had limited resources and was itself controversial. The committee would later be criticized for various excesses, which may have undermined its credibility when pushing for prosecution of prominent citizens.

Historical Debate and Legacy

Historians remain divided about the Business Plot. Some, like Jules Archer in The Plot to Seize the White House (1973), argue that a genuine conspiracy existed and that Butler prevented what could have been a successful coup. Others suggest that while MacGuire and his associates may have entertained fantasies about organizing veterans to pressure Roosevelt, the “plot” never amounted to a serious threat to overthrow the government.

What remains undisputed is that:

- Butler was approached by MacGuire and others

- These approaches involved discussions about organizing veterans

- MacGuire had financial backing from wealthy businessmen

- The McCormack-Dickstein Committee found the allegations credible enough to issue warnings

The affair reveals the intense anxiety among American business elites about Roosevelt’s policies and the extent of class conflict during the Depression. Many wealthy Americans genuinely feared that the New Deal represented socialism or communism, and some were willing to consider extreme measures to counter it. That these fears led even to discussions of a coup—however serious or fanciful—demonstrates how fragile democratic institutions can become during times of economic crisis.

For students of American history, the Business Plot serves as an important reminder that democracy is not inevitable and that even in the United States, there have been moments when powerful interests contemplated authoritarian alternatives. It also raises important questions about accountability and justice: when powerful people escape consequences for their actions, what message does that send about equality under law?

General Butler, for his part, spent his remaining years speaking out against war profiteering and corporate influence in government. His decision to expose the plot rather than profit from it stands as a testament to civic courage. In his words: “I helped make Mexico safe for American oil interests. I helped make Haiti and Cuba a decent place for the National City Bank boys to collect revenues in. I helped purify Nicaragua for the international banking house of Brown Brothers. I brought light to the Dominican Republic for American sugar interests… Looking back on it, I feel I might have given Al Capone a few hints.”

Whether the Business Plot was a genuine threat to American democracy or an overblown scheme by delusional businessmen, it remains a fascinating episode that deserves more attention in our understanding of the 1930s and the fragility of democratic institutions.

For further reading, see the McCormack-Dickstein Committee Report (1935), Jules Archer’s “The Plot to Seize the White House,” and Smedley Butler’s “War Is a Racket.”

This is part of my Readings In History series. Where I try to collect resources from historical events and pop culture to talk about and discuss in my classes. To see more of these entries click here.

You must be logged in to post a comment.